It is troops that go to war and Generals take the credit, so goes a common adage. A famous military general to much acclaim did both; he led from the front on the ground, and got credit for the victory.

The story of Gen. Mohamed, who retired as Chief of General Staff, cannot be told without talking about the small “disturbances” that erupted in 1982.

The casual manner in which the coup – spearheaded by junior officers of the Kenya Air Force, was planned makes it a laughing stock at any military academy on the planet. The junior officers’ body of plans made a perfect blueprint of how not to stage a coup.

But let’s start from the beginning sometime in 1981, Kenya’s spy chief Kanyotu (pictured above) and top soldier Gen. Mulinge became aware of plans to stage a mutiny in the military — mostly in the Air Force. Morale in some sections was low and there were allegations of tribalism.

Gen. Mulinge realized how grave matters were when he accompanied President Moi in inspecting a guard of honour later in 1982. As they filed past the Kenya army guard and onto the Air Force “quarter guard”, Mulinge noticed something about the airmen that bothered him immensely. The junior air force personnel made mocking faces at their commander in chief.

Later that day, Gen. Mulinge updated Kanyotu on the development. Moi was also reportedly shocked and sought to know if all was well with the military. It is not known what answer Moi got from Gen. Mulinge. What was clear was that things were not well.

Meanwhile, as Kenyans came to learn later, covert meetings started taking place away from the barracks between junior air force personnel and individuals perceived to be dissidents.

Sections of the Air Force started scheming for the final execution plans of a coup. Come July, both the special branch and military intelligence had confirmed that there were advanced plans to stage a coup.

In an interview with veteran scribe Roy Gachuhi, former army commander Lt. Gen. (Rtd) Humphrey Njoroge laid out never disclosed details about the coup plot, and the counter-action that ensued, spearheaded by mostly infantrymen.

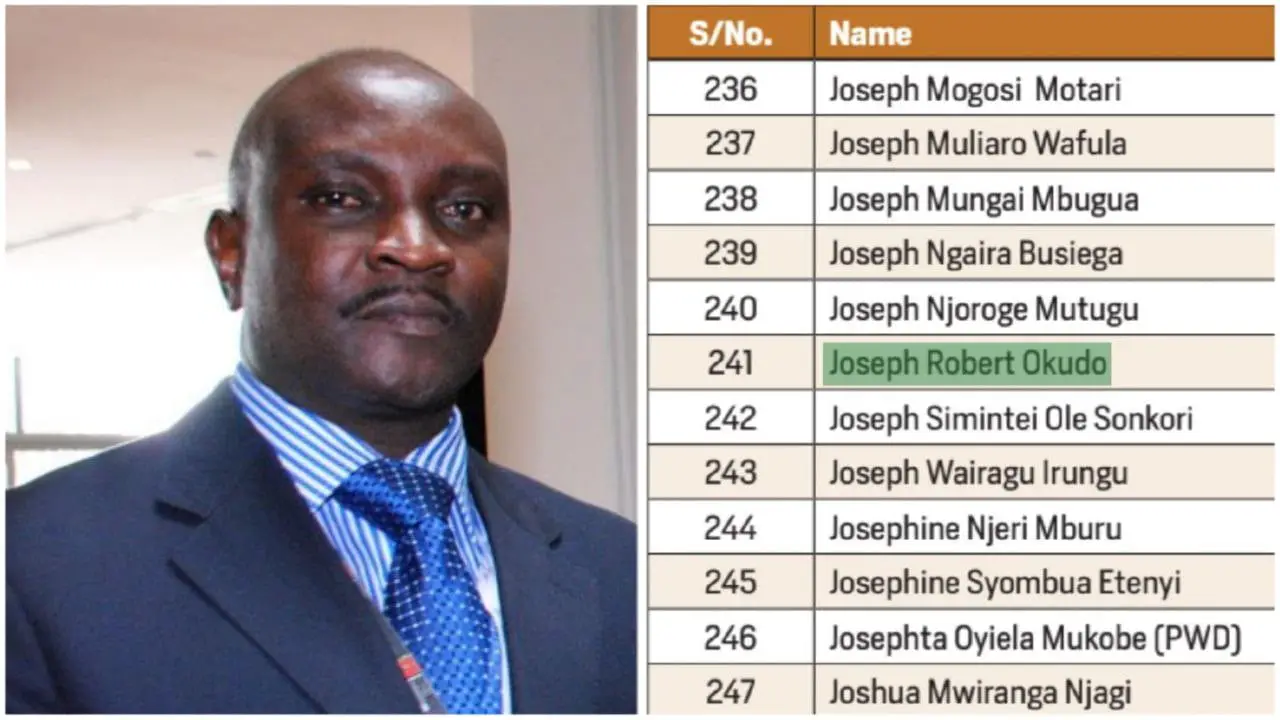

A few days before the coup, Kanyotu sought authority from President Moi to arrest junior officers of the Air Force among them Sergeant Joseph Ogidi, Corporal Walter Ojode, Corporal Bramwell Njeremani, Corporal Charles Oriwa, among others.

Moi’s was an unusual cautious approach. At the time, the Special Branch was a division of the Kenya Police. Moi was cautious not to create the impression that policemen had been sent to arrest military men.

He preferred that the military police handle the matter themselves the following week, which coincided with the start of August.

What Moi didn’t realize was that the coup attempt was just simmering. The Air Force men were also aware that most of the army formations were in Lodwar for war games. The timing was perfect.

On the eve of the coup, junior airmen got into an orgy of drinking. This was on Saturday night leading to Sunday, 1st August 1982. The first bursts of rebel gunfire were heard from the air force base inside the old Embakasi airport. The gunfire, however, wasn’t aimed at anyone in particular.

Rather, the drunk Air Force NCOs, who were awaiting word from their leaders on when to kick off the coup, rather foolishly started bursts of loud machine gun fire aimed skywards.

So loud and intense was the gunfire that Embakasi police heading to the scene in response to calls from terrified civilians had to turn back.

Scared, the police radioed headquarters, saying that the intensity of gunfire they heard was like nothing they had ever responded to. The source of the gunfire, they reported, was the military base inside the airport.

At this time, the whereabouts of both President Moi and Gen. Mulinge were unknown. By midnight, the Air Force men had already surrounded and taken over Voice of Kenya, announcing on the airwaves that the government was in the hands of the military.

At the same time, three independent loyalist teams were already scheming on how to scuttle the coup – the army, special branch and the police.

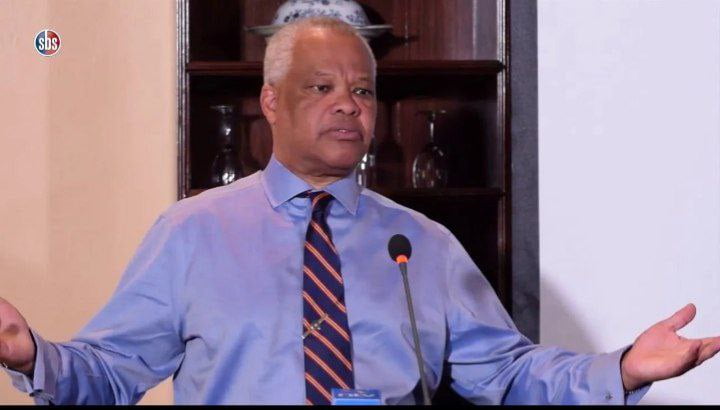

A team of senior officials led by army commander Lt. Gen. Sawe and his deputy Maj. Gen. Mahmoud Mohammed were summoned in the dead of night for a meeting to plan a counter.

Lt. Gen. (Rtd) Njoroge (pictured), then an army major, was among them. Being the junior-most officer present, his was to take notes of the meeting. According to Njoroge, Mohammed didn’t have the patience at that meeting of an elaborate plan.

That army units were far off inching towards Nairobi from the war games in Lodwar was a concern. A rapid counter-execution was required. Mohammed asked his boss, Army Commander Lt. Gen. Sawe, that he be allowed to take charge of the operation to take out the airmen and restore sanity.

Perhaps inspired by the boldness of his deputy – a streetwise, ill-educated but battle-hardened (Mohammed served in the Ogaden war) man who had joined the army in the 1950s, Sawe granted him the go-ahead.

It must have been past 3am when Mohammed marched off to execute his orders. At around the same time, Chief Secretary Jeremiah Kîereînî rushed to Vigilance Hours to join GSU Commandant Ben Gethi. From here, for the next 24 hours without food or drink, the duo would frantically coordinate responses to quell the coup.

Gethi would later – to his shock, be among officers purged after the coup. Meanwhile, from a safe house location, away from Nyati House, then the famous headquarters of the Special Branch, Kanyotu and his men were about to throw the airmen into disarray.

From this secret location, Kanyotu started coordinating the jamming of Air Force signals for much of the duration of the coup. By daybreak, Mohammed had gathered a few men from 1KR and 7KR. It wasn’t time to storm the Voice of Kenya yet. He felt he still needed more men. So he devised a plan that he only shared with then Maj. Njoroge. A plan that was largely based on deceit.

Meanwhile, far away at Laikipia Air Base, three jet fighter pilots – Baraza, Mugwanja and Mutua – were about to pull off a different kind of deceit. Earlier, as the three pilots relaxed at home with their families, rebel servicemen at the airbase loaded armaments and high explosive bombs onto three fighter planes.

They later rounded up the three pilots at gunpoint and ordered them to suit-up. The rebels were acting under instructions of the coup leader, Snr. Pvt. Hezekiah Ochuka (pictured below), who wanted both State House and GSU Headquarters blown into smithereens.

They wanted two F-5s and one strike master jet to do the job.

Occupying the rear seat, Cpl. Bramwel Njeremani boarded Mutua’s 2-seat F-5 jet fighter and commandeered him at gunpoint. Similarly, the other two pilots were under instructions to obey the instructions or else get themselves and Mutua killed. But Mutua and his co-aces had a plan.

They knew Njeremani had no prior jet-flying experience and that the F-5 jet acrobatic manouvres would giddy him up and possibly even kill him.

Lt. Gen. Njoroge described to Roy Gachuhi what happened; “Mutua knew that Njeremani wasn’t going to survive these pressures. After the first run, the gun dropped out of his hand. To ensure that Njereman was enduring maximum discomfort, Mutua kept asking him questions such as: ‘What can you see? Where is that?’ The exposure to so much g-forces was taking a heavy toll on Njereman but Mutua kept talking to him to tire him further. After three runs, the gunman could barely speak. It was safe to make the trip home.”

For a bomb dropped from an aircraft to explode, the pilot must first arm it before releasing it from the plane’s under-wing hold. If he releases it unarmed, it will simply drop to the ground like a stone.

That procedure is called dumping. Njeremani had no way of knowing that the bombs earmarked for State House and GSU HQs had been dumped at Mt Kenya forest (which is what happened).

Back at the (Laikipia) Base, he looked dizzy and confused as he staggered out of the jet. He announced to other servicemen that they had bombed Nairobi. But by that time, the Army was closing in on the Base.

Gen. Mohammed was busy coordinating units taking over Embakasi and Eastleigh air bases. If I recall correctly, it was Laikipia and Embakasi that fell in that order. The battles of Eastleigh and VoK, the takeover of which Mohammed was leading, were far from over.

Below follows an account based on Roy’s interview with Lt. Gen (RTD) Njoroge:

“In those days, he who called the shots at KBC, then known as Voice of Kenya, owned the country. Unlike what’s the case today, then there were no other source of instant information.

The first target for all African coup makers was the national broadcaster and Kenya’s rebel airmen were working to script.

The convoy was readied and Njoroge took his seat in the first Land Rover. Mohammed took his in the second one and the others lined up. Then the convoy rolled out of Army Headquarters and headed for Argwings Kodhek Road. It then turned left at the Silver Springs Hotel round-about and joined Valley Road. The operation to save Moi from his own catastrophic error had begun.

The convoy cruised down Valley Road, getting into Uhuru Highway, then University Way and onto Harry Thuku Road where they headed for VoK (now KBC). Other vehicles followed. All over town were rebel soldiers and university students shouting “Power!”.

Says Njoroge: “Whenever we encountered them, we shouted “Power!” and punched the air with our fists. A lot of looting was taking place already. There were huge celebrations by university students around Broadcasting House, and there was loud music. Just outside the Norfolk Hotel, they stopped and Njoroge, resplendent in his doctor’s coat, stepped out of his vehicle and went straight to the VoK gate. Everybody else remained behind. He recalls: “There were very many rebels there and they were armed. I identified a man who wore a general’s ranks on both his shoulders. On one shoulder was air force insignia and on the other army insignia. It was a bit dark.”

He approached that “officer” and told him: “We are from Memorial. We are here to help you.” He was referring to the Armed Forces Memorial Hospital and made sure the “officer” saw the line of ambulances parked outside the gate.

The officer looked pleased and said: “Good. Carry on.” The encounter lasted less than five minutes but that was all Njoroge needed to survey the field. He walked briskly back to the Land Rovers.

He says: “I have reason to believe the man I spoke to was Ochuka. I did not know him and neither did he know me.

I will never be sure, but something told me I had just spoken to the coup leader who from later accounts turned out to be there at that time. There was something in his demeanour that made him stand out from the rest.”

Back to where the Land Rovers were, Njoroge told Mohammed: “Sir, we cannot attack them. They are too many and they are well armed. Even if we succeed in overpowering them, we do not have an exit corridor. We cannot leave and no reinforcement can reach us. We shall be trapped here.”

He suggested they go to Kahawa Garrison and seek reinforcements. He also said they should contact the Embakasi-based 50 Air Cavalry Battalion to create a corridor when it was time to withdraw.

Mohammed asked him: “Are you sure this is what we should do?” Njoroge affirmed and remarked: “Mohammed is a good senior officer who listens to good advice. He is not opinionated. He just said, ‘OK, let’s go.’”

The convoy headed to the Globe Cinema round-about and took Murang’a Road and drove to Kahawa Garrison where it arrived around 6.30 a.m.

At the gate, they learned that Sawe had issued firm instructions that nobody should be allowed in or out of all military bases in the country. They were thus stopped by the sentries and flatly denied entry. A furious Mohammed walked up to Cpl Halake, the sentry in charge and asked him whether he knew who he was. Halake politely told him yes, he knew he was the Deputy Army Commander, but no, he was not going to allow him in. His instructions from Gen Sawe, he politely told Mohammed, did not exempt anybody, sorry sir.

Mohammed cocked his gun and thundered: “I am going to shoot you!”

Looking at the angry boss and perceiving the company he was in, the sentry relented and opened the gate. There wasn’t any doubt in Njoroge’s mind that Mohammed meant his threat.

The convoy rolled in. Garrison Commander Col Njiru was holed up in a meeting with his officers while the troops were in their quarters.

Mohammed took charge of the meeting. There were two officers from his previous command at 1KR who he particularly liked and wanted to accompany him – Maj. Wanambisi and Maj. Kithinji.

Two others, Maj. Cheboi and Maj. Kiritu from Langata, would also play crucial roles in his scheme of things.

“He wanted people he could trust,” Njoroge says. “These obviously had to be people he knew very well.”

Mohammed told the gathering that he wanted the troops gathered and the top shots who had won trophies during the armed forces rifle championships identified.

That done, Maj Wanambisi was assigned the vanguard group and Maj Kithinji the back-up. Weapons were then distributed. Depending on their specialties, the troops were given submachine guns, G3 rifles and light machine guns. Nobody was told what the mission was.

The convoy then headed back to the city through Thika Road, Forest Road, past Parklands Secondary School, Forest Lodge before finally stopping at the Museum Hill round-about.

That is where the final briefing took place and it is where the troops were finally told what their mission was.

Said Mohammed: “Tunaenda VoK na tunaenda kufa.” (“We are going to VoK and we are going to die”).

He then told them the plan was to make the rebel airmen surrender peacefully without a fight. But the orders were to return fire when fired upon or to fire in pre-emptive self-defence.

This is exactly what happened in literally the next instant.

Just as the briefing was about to end, one Private Odero saw an airman take aim at Mohammed who was standing prominently in front of the troops.

Instinctively, he let out a burst of machine gun fire that felled the airman and several others standing near him. At that point, the plan changed. It became a full scale assault.

Abandoning their vehicle after their final briefing, Mohammed’s troops inched towards the broadcasting station slowly, the crack shots taking out drunken air force servicemen one after the other.

According to Njoroge, when it became apparent that the airmen were under siege, an airman exclaimed: “Kwanini GSU wanatupiga?” (“Why are the GSU overpowering us?”)

He was under the mistaken impression that the attackers were GSU officers because the coup had been timed to take place when the Army was out of town.

Coupled with the fact that the southern entrances to the city were blocked by airmen from Embakasi, the airman was sure these troops, coming from the direction of Westlands, could only be GSU personnel.

The Army force from Kahawa numbered less than 30. But it exacted a huge toll among the drunken airmen, who were partying with university students. The actual number who died in the assault may never be known, but it was reliably estimated to be between 100 and 200.

At that time, there was no perimeter wall around the broadcasting complex. The invaders were therefore able to enter from Uhuru Highway. The first soldiers to reach the radio studios killed five rebels inside there.

They then went back and told Mohammed, who was close behind, that the route to the studio was clear and Leonard Mambo Mbotela (pictured), the famed broadcaster who had been kidnapped from his house and forced to announce Moi’s ouster, was still inside.

Mohammed strode in, Njoroge with him.

“I am General Mohammed,” he told Mambo, “I want you to announce that Nyayo forces have retaken the country.” Njoroge, who kept taking notes of every detail of the operation, then gave Mambo a list of officers whose names he was to broadcast as being at the station.

These were Maj-Gen Mohammed, Maj Wanambisi, Maj Kithinji, Maj Kiritu, Maj Cheboi, Maj Mulinge and himself, Maj Njoroge.

Hello then went to the library and fetched a gramophone record, Safari ya Japan by Joseph Kamaru. “Play this,” he told Mambo, who did. The record and the composition of the list of soldiers were meant to reassure soldiers everywhere that Nyayo was indeed back in the saddle.

“It was a psychological ploy,” he says. “Not all the officers whose names I gave Mambo to read were at Broadcasting House.”

Outside the station, the assault had turned into a chase and mop up operation. Airmen were fleeing in numbers. But Ochuka, Njoroge was to learn later, was still insisting he was Commander-in-Chief.

Through the armed forces communication system, he kept insulting Sawe and threatening him with dire consequences for resisting. It was then that Sawe ordered the army’s MD500 helicopters to blow up the communications facility at the Eastleigh air force base. Without communications, Ochuka’s coup collapsed and he was soon on his way to Tanzania.

It was not until about 3 p.m that the invading party was relieved from Defence headquarters. Accompanied by Njoroge, Mohammed then went to DoD to find Mulinge, Sawe and a few other senior officers.

The gathering embarked on mop-up plans. But first they had to get a devastated Moi, who had been brought to town in an armoured convoy from Kabarak led by Maj Gen Musomba, to announce to Kenyans that he was back as President. Few Kenyans who watched him on TV that evening will forget the crushed look in his face.

Moi was not to be the same man again. Following a court martial, Ochuka and a number of coup plotters were hanged in 1987, by which time a massive purge of the Kenya Air Force had been undertaken.

Dozens of civilians lost their lives during the disturbances. Many others were arraigned in court for petty crime and looting of business premises, which took place at a massive scale particularly in Nairobi’s CBD and Ngara areas.

Gen. Mohamed was moved from the army to head the new Airforce outfit. Later on, in 1986, he was appointed Chief of General Staff.